Ash Bhardwaj’s cultural Costa Rica

Cultural experiences in Costa Rica are certainly not hard to find. With its volcanoes, jungles and beaches, it is tempting to think of Costa Rica as just an adventure destination. But, as Ash Bhardwaj found out, Costa Rica has a rich cultural heritage, which is just as accessible as its wilderness. Here are the stories of four people Ash met in Costa Rica…

1. Jindra

“What are we cooking?” I ask.

“Caribbean jerk chicken,” says Jindra, my teacher and host for the evening, “With a little Costa Rican twist.”

It’s easy to think of Costa Rica in terms of just its Spanish and indigenous heritage, but there’s another cultural influence, too: the vibrant Afro-Costa-Rican community on the country’s Caribbean coast.

People of recent African descent first came to Costa Rica with the Spanish conquistadors, and many more were brought here as enslaved people until slavery was abolished in 1823. But the largest proportion of Afro-Costa-Ricans came here from Jamaica for work in the late 19th century.

The Jamaicans settled around Limon and spoke very little Spanish, retaining their culture, language and cuisine. I went to the town of Puerto Viejo to learn more about this culture by learning how to cook jerk chicken with Jindra. As we cooked, the smell of thyme and lime emanated from the pot, filling the room with a warm, spicy haze.

“Black people, white people, Indian people – we all have our cultures in Costa Rica,” says Jindra. “That is what makes Costa Rica so interesting. And we each have our own foods, which is why Costa Rica is so tasty!”

Jindra’s jerk chicken is made with fresh Panamanian peppers, onions, tomatoes, and Salsa Lizano – a thin, brown Costa Rican condiment that’s somewhere between HP Sauce and Worcestershire Sauce.

“So, it’s Caribbean food, with a Costa Rican twist,” she said. “Just like the black people in Costa Rica!”

My role was mere chopper of tomatoes, which I poured into the pot once the chicken started to brown. The Panamanian peppers stung my eyes, but the feeling was more than worth it when I sampled the tangy sauce.

“You like it?” asked Jindra.

I could only nod in satisfaction.

“Good,” she said. “If you eat Caribbean food, it will give you Caribbean spirit.”

2. Ishmael and Olmer

Not far from Puerto Viejo, but only reachable by road, track and river, is the village of Yorkin. It is part of a reservation belonging to the Bribi; an indigenous group whose remoteness helped them avoid conquest by the Spanish, and helped them retain their language and customs, too.

To reach the village, we took a dugout canoe along the Yorkin River, which separates Panama from Costa Rica. The air was warm and humid, but there was a breeze coming down the river, made stronger by the movement of the boat.

“The Bribri are animists,” said local guide Ishmael. “The mountains, trees and rivers are sacred to them. So is the cacao plant, which is also their main source of income.”

As we headed upstream, our navigator, Olmer, sat in the bow, shouting to the pilot on the tiller, who guided the boat through the rapids. When the water got too shallow, we jumped out. Usually it was no deeper than my shins, but I got a refreshing dip when I slipped whilst pulling the boat over a rock shelf. I plunged in up to my waist, much to the amusement of Ishmael and Olmer.

A few minutes later and we reach the village, where most houses have traditional palm-frond leaves. All around us were indigenous farms which, to the untrained eye (including mine), looked like an extension of the jungle.

“They are a mix of crops,” said Ishmael. “Western farming is monocultural – just one crop. That’s bad because it exhausts some nutrients in the soil and wastes others.

“Indigenous farming is multi-crop. Each crop adds and takes different things from the soil. They all flower and fruit at different times, too, so the farms produce all year round. This means you have a farm that prevents erosion, is more sustainable, more efficient, and needs less land than mono-crops.”

This multi-crop farming technique is used in other parts of Costa Rica, too. Coffee is an introduced crop, but it thrives in the mountains, with tropical temperatures and regular rainfall.

When coffee bushes are planted beneath banana trees, they have the benefit of shade, which helps them grow more evenly, and extra potassium fixed in the soil by banana trees. Parasitic nematodes feed on banana roots instead of coffee bushes, and insect-eating birds prefer the varied vegetation, reducing the need for pesticides.

3. Ezekiel

Indigenous cultures influence the west of the country, too. The Nicoya Peninsula is known for its surf beaches and resorts, but it is also a Blue Zone – one one of five places on earth where people commonly live to the age of 100. Nicoya’s indigenous heritage is thought to be a contributing factor.

The Chorotega settled in northern Nicoya some 1,500 years ago, having escaped slavery in Mexico. As such, their culture has more in common with the Maya peoples of Mesoamerica than with the Bribri of southern Costa Rica. One example of this is the wide cultivation of maize in northern Nicoya.

“We get two crops a year,” said Ezekiel Aguirre Perez, “And we make many foods from it, including tortilla, pozol soup and pinol [ground roasted maize flour]. We won’t eat meat every day, and we eat a lot of vegetables.

“But the biggest thing is ‘Mano Vuelta’ – community spirit. When we build a house, everyone comes to help. Then, when someone else builds a house, we all go to help them. Always helping, and always being helped. That is real community.”

As we walked around the town of Matumba, where many Chorotega live, people said hello, asked me my name, and wished me a good stay. Kids held hands as they walked between houses, picking up friends to play football next to the schoolhouse.

“The climate means our houses are open,” said Ezekiel, “And people sit on porches. They walk around, and they interact. They meet people of all ages, and they stay active. All of this means we live long, healthy lives.”

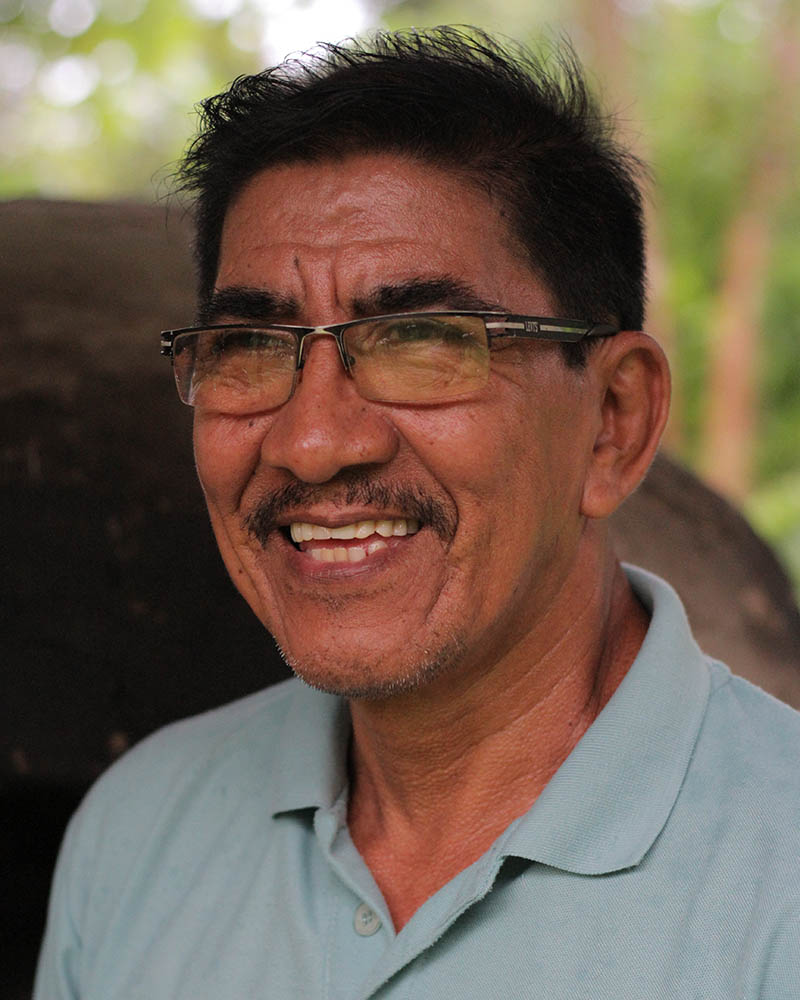

4. Pachito

Nowhere does this seem more true than with Pachito, who had recently turned 100. When we arrived, he was coming down the hill on his horse, and he dismounted onto the porch before welcoming us.

“Sorry,” he said. “I’ve been visiting some of my poorly friends. When I’m sitting down everything hurts, so I get on the horse and go out for half an hour, and try to cheer them up. Besides, I’ve been a sabanero [a Costa Rican cowboy] all my life, so horse-riding is as natural to me as breathing.”

On his walls were birthday cards from friends, great-great-great grandchildren, politicians and doctors, as well as an invitation to the Nicoya centenarian event, to celebrate those who have reached their hundredth year. I wondered what it was that led Pachito to such a long and vibrant life.

“When I was young,” he said, “Money was scarce and life was difficult, and there were no doctors in the region. But the land was good. We ate cacao and rice, and sometimes chickens. We ate what we grew, or what we hunted, so we knew where it was coming from, and that it was pure and healthy.

“There’s also spirit,” he continued, “During my life, I haven’t been a great person, but I’ve always been a good friend. You have to love yourself, and love God, and also love others. Because if you love others, you can’t wish anything bad on them.

“And then there’s the “Plan de Vida” – a purpose. I still go to bed at sunset, and wake up at dawn, then visit my friends. I’ve kept fit by just doing what I do – being active and riding a horse. I still help with farming where I can. Other people keep their purpose by getting up early to bake tortillas, then walk five miles into town to sell them. We feel like we can contribute, even when we are older, and that is what keeps us alive. Pura Vida!”

As I waved goodbye to Pachito, I wondered if I could create my own Pura Vida back home. I can’t do anything about the sunlight hours or calcium in the water (both of which are thought to improve longevity), and horses are impractical for commuting around London. But I’m sure I could find more purpose in seeing friends.

I’m not the first person to come here looking for the elixir of long life. For all of the scientific interpretations, Pachito knows what the simple answer is: just spend more time in Costa Rica.

Pura Vida, indeed.

Ash Bhardwaj

Ash is a travel-writer, filmmaker and storyteller who explores the world with curiosity, excitement and a sense of adventure. During his time in Costa Rica, he enjoyed soaking up the rich culture as well as taking part in the thrilling adventures on offer such as ziplining.

Find your next adventure in Costa Rica:

How to experience Pura Vida in Costa Rica

Here’s 7 ways to get the heart racing in Costa Rica

Chloe Gunning shares her top Costa Rican adventures with us